Historical fiction, real history and the past on repeat

I go nowhere without a book, in whatever form. And now, more than ever, a good book provides refuge from obsessing about how to stop the authoritarian takeover of the United States.

I devour historical fiction thrillers, crime, mystery and adventure, from authors such as Bernard Cornwell and CJ Sansom, to name two of my favorites.

Cornwell’s Richard Sharpe, the hard-scrabble hero in the British army from 1799 through the Napoleonic Wars, is my favorite of his series, with the rebellious Saxon Lord Uhtred of Bebbanburg hard on his heels, in the “The Last Kingdom” series.

Matthew Shardlake is Sansom’s deeply humane Tudor era protagonist, a London barrister living with a spinal disability, disparaged then as a “hunchback.” He is charged with carrying out Thomas Cromwell’s orders, beginning with the dissolution of the monasteries, but solves murders and mysteries along the way, with engaging companions.

I’m always looking for the next book, or better yet, the next series, in these genres. Other authors and protagonists I love include Philipp Kerr’s pre-and post-war German detective Bernie Gunther, Volker Kutscher’s “Babylon Berlin” series and Alan Furst’s 20th century spy thrillers.

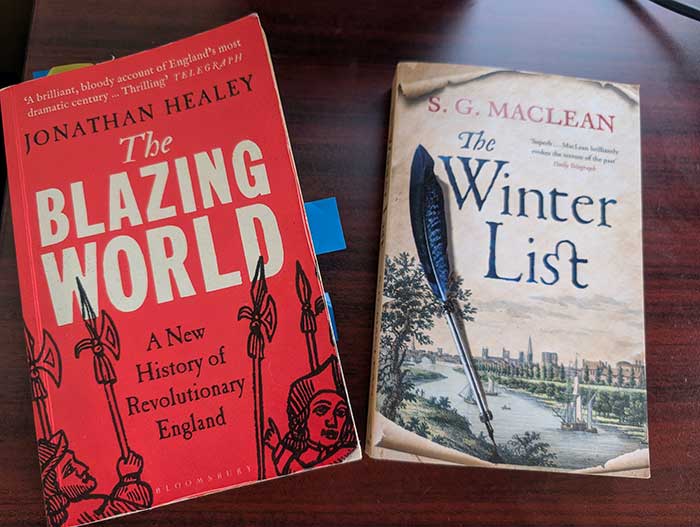

Last summer I discovered two (!) series by the Scottish writer S.G. MacLean. The Alexander Seaton series takes place in the first third of the 1600s, and the Damien Seeker series is set during the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell and the first year of the Restoration. I read the first book of each series and then promptly put the rest of the books on my wish lists. On my birthday I opened a gift-wrapped box with every book on my wish list, and I’ve been hoarding and spacing out my reading of them, for the past eight months, savoring each one.

Cornwell, Sansom and MacLean have also written stand-alone books that I have enjoyed.

Fuzzy on Oliver Cromwell, though

I’m well-read on some of these eras, and had studied some of them in college, but realized on book four of Damien Seeker, “House of Lamentations,” that I was fuzzy on the events and timelines of the English Civil Wars and the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell. That’s when I ordered “The Blazing World, a New History of Revolutionary England,” by Jonathan Healey. Healey is an associate professor in social history at Oxford University and an expert on the 16th and 17th centuries. This is a deeply researched and readable history of the chaotic years from 1603 to the early 1700s, and I will be reading the last Seeker book, “The Winter List,” with a much better understanding of the world this character inhabits.

The past is not prologue

Lately the novels I read feel less like safe, distant stories of heroes conquering their enemies in past wars and battles and more like warnings of how societies repeat the same mistakes, century after century, millennia after millennia.

With apologies to Shakespeare, I don’t believe the past is prologue, but repetition. It seems to me that collective memory lasts about 70 years, and then, when the people who lived through earlier cataclysms die, we stumble into the same fatal, cyclical traps. Lessons learned by one cohort are not permanently imprinted for future generations.

I see societies continually trying to solve the same basic problems of living, just with newer versions of the same solutions. When men want power and wealth, they take it and keep it by dominating ordinary people with fear of others, threats of religious judgment and violence. Ordinary people want safe, healthy, contented lives and freedom to make their own choices for happiness.

Arguments over religious practices, supreme authority, and economic practices, such as unfair taxation, Royalists versus Parliamentarians, boiled over into the English Civil Wars. These resonate with me as those who have taken charge of the United States crush our values and freedoms, and seek to install an absolute ruler instead of an elected chief executive. While we naturally think of Hitler and King George III, we can also see the patterns in 17th century Britain.

We the people

The 17th century anticipated America’s founding principle of “We the people,” as “a debate over sovereignty ran through the century,” Healey writes.

“Even before the Civil War, the Parliamentarian Propagandist Henry Parker had argued that ‘Power is originally inherent in the people,'” while in 1650 an unrelated theorist, John Parker, argued that “government ‘is in the people, from the people, and for the people.'”

Of course this philosophy, which Parliament represented, was not compatible with the absolute monarchy that King Charles I demanded.

Sliding into division

Healey writes, “In Canterbury, one Royalist minister worried, ‘We can hardly look upon each other in charity.'”

He quotes lawyer Bulstrode Whitelock’s horror at “how we have insensibly slid into this beginning of a civil war, by one unexpected accident after another, as waves of the sea.’ ‘We scarce know how, but from paper combats….we are now come to the question of raising forces, and naming a General and officers of our army.'”

From Aug. 22, 1642 to Sept. 3, 1651, an estimated 190,000 of a population of 5 million, died of disease or in battles in the English Civil Wars. After the execution of Charles I in 1649, the House of Commons led the Commonwealth of England until 1653. Cromwell served as Lord Protector from 1653 to his death in 1658, followed briefly by his son Richard and the Restoration of the monarchy in 1660.

The never-ending question of voting rights, immigration and holding leaders accountable to the law

Cromwell’s rule had raised new questions about governance that speak to Americans’ concerns about voting rights and about gerrymandering. Who should have the right to vote? All men, or only property owners? Should a poor, unpropertied man with no vested interest in the state be able to vote? Healey quotes Thomas Rainborough, who argued that he found nothing “‘in the law of God that said that a lord shall choose 20 burgesses and a gentleman but two, or a poor man shall choose none.'” Rainborough, Healey notes, wondered “‘what we have fought for, is it a law which enslaves the people of England that they should be bound by laws in which they have no voice at all?'”

Also relevant to our times, Healey quotes philosopher John Locke on the benefits of immigration, “‘for it is the number of people that makes the riches of any country.'”

“What can the people do if their leaders break that law?”

What is the root of lawful government, Healey asks? “By the end of the 1640s, many on the more radical wing of the old Parliamentarian cause had come to the conclusion that laws and government originated in the people, and that kings were only useful if they protected the people.” Healey notes that by the end of the 17th century, it was “settled principle” that kings must be accountable to the law and to the people.

Which brings us around to America’s current battle against tyranny. Trump’s vision of a king who doesn’t protect, but threatens the people, and who runs rampant thanks to dubious superior criminal immunity, is not useful to the people. We have plenty of lessons from history about the dangers we face. We should be able to stop this would-be absolute ruler without destroying the people. But the institutions are only as strong as the honor and morality of their leaders, and the power of the people’s historical memory.

America’s mistake was in thinking we were too smart and evolved to fall for it.

I’m not a historian, nor any kind of expert of the English Civil Wars, and apologize for any errors of fact or misquotations. I welcome corrections. If you’re interested in learning more or reading any of these authors, please visit their websites linked in this post and choose the bookseller or the library you prefer.